University of Edinburgh-led team discovers new species of dinosaur

The species had one less finger on each forearm than its close relatives, suggesting an adaptability which enabled the animals to spread during the late cretaceous period.

Multiple complete skeletons of the new species were unearthed in the Gobi Desert in Mongolia by a University of Edinburgh-led team.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

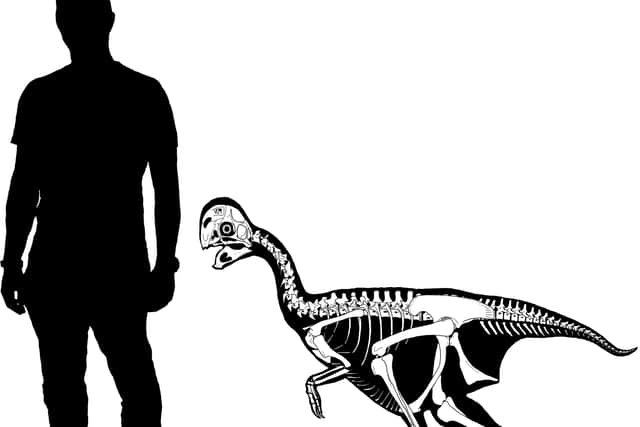

Hide AdNamed Oksoko Avarsan, the feathered, omnivorous creatures were around two metres long, had only two functional digits on each forearm and a large, toothless beak similar to the type seen in species of parrot today.

The well-preserved fossils provided the first evidence of digit loss in the three-fingered family of dinosaurs known as oviraptors.

That they could evolve forelimb adaptations suggests they could alter their diets and lifestyles and enabled them to diversify and multiply.

Researchers studied the reduction in size, and eventual loss, of a third finger across the oviraptors’ history.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe group’s arms and hands changed drastically in tandem with migrations to new geographic areas – specifically to what is now north America and the Gobi Desert.

The team also discovered that Oksoko Avarsan – like many other prehistoric species – were social as juveniles.

The fossil remains of four young dinosaurs were preserved resting together.

Dr Gregory Funston, of the University of Edinburgh’s School of GeoSciences, who led the study, said: “Oksoko Avarsan is interesting because the skeletons were very complete and preserved resting together, showing juveniles roamed together in groups.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“More importantly, its two-fingered hand prompted us to look at the way the hand and forelimb changed throughout oviraptors evolution – which hadn’t been studied before.

“This revealed some unexpected trends that are a key piece in the puzzle of why oviraptors were so diverse before the extinction that killed the dinosaurs.”

The study, published in the journal Royal Society Open Science, was funded by The Royal Society and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Council of Canada.

It also involved researchers from the University of Alberta and Philip J. Currie Dinosaur Museum in Canada, Hokkaido University in Japan and the Mongolian Academy of Sciences.