It is 225 years ago since Borders explorer set sail in search of the Niger

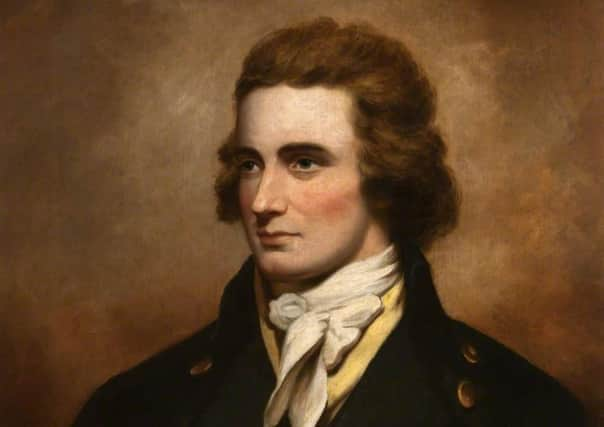

So what drove an ambitious young man, born in 1771 to a tenant farmer in the Yarrow Valley, to venture into lands unknown to Europeans and why was the River Niger so important?

This was the Age of Reason, a time where people were probing nature’s secrets and questioning previously held beliefs.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdKnowledge of world geography was expanding and maps of countries and continents that might once have had vast expanses with little or no detail were showing physical features.

The one exception to this was the interior of Africa.

Established in 1788, the African Association became preoccupied with tracing the course of the River Niger, a mighty river Europeans had heard of but not seen.

The coastline of Africa, especially the west coast, was well known to European traders – particularly those involved in the slave trade.

But the coast presented challenges with few natural harbours. The search for the Niger was as much about accessing the interior of Africa for trade and exploiting its natural resources as exploration.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

Mungo Park spent his childhood in the Yarrow Valley and Selkirk before studying at Edinburgh University where he qualified as a surgeon.

After a spell with the East India Company he approached the African Association.

He said: “Soon after my return from the East Indies in 1793, having learned that the noblemen and gentlemen, (of the African Society) associated for that purpose of prosecuting discoveries in the interior of Africa, were desirous of engaging a person to explore that continent by way of the Gambia River … I offered myself for service.”

The African Society commissioned Park to travel inland, find the River Niger and follow its course until it flowed into the sea.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLeaving Britain in May 1795 Park’s ship arrived at Jillifree, a town on the River Gambia, on June 21, 1795, and from there he headed inland to Pisania (now Karantaba).

Here he spent five months acclimatising, learning some of the local languages and culture and waiting for the end of the rainy season.

Noting that earlier expeditions sponsored by the African Society had been unsuccessful, Park planned a very different tactic and believed that, “a traveller of good temper and conciliating manners, who has nothing with him to tempt rapacity, may expect every assistance from the natives and the fullest protection from their chiefs”.

Therefore, in late 1795, Park set out on horseback with food for only two days, an umbrella, a sextant, a couple of rifles and pistols, beads, amber and tobacco.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe was accompanied by two Africans, both ex-slaves, as guides and companions.

The idea was that by not going as part of a large group he wouldn’t be seen as a threat and if he did not carry much then he wouldn’t be attacked and robbed.

Park kept a journal and on his return to Britain it was published; Travels into the Interior of Africa became a bestseller.

The book records his travels from township to township, the cultivation of crops, the husbandry of livestock and the fauna and wildlife he observed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDespite Park’s best endeavours to explain that his only purpose was exploration and not trade he was rarely believed.

The Africans couldn’t comprehend that the purpose of anyone’s journey could be to look on a river.

Was one river not the same as another? Were there none in his own country?

Although his treatment by the Africans was generally one of friendship, he also suffered great hardships. But Park always recognised good as well as bad.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe was non-judgmental and it has been suggested that his attitude to, and treatment of, the Africans was similar to that of David Livingstone.

Both came from humble origins so they could easily associate with the Africans’ struggle to survive in often inhospitable conditions.

This may account for Park’s lack of arrogance and assumptions of superiority, characteristics not displayed by many who followed him.

But when Park arrived in the Kingdom of Ludmar, he was imprisoned for three and a half months and his companion taken as a slave.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn June 28, after fearing he may be executed, he escaped. However, he was alone in the bush with no food or water.

Park’s journal relates how he had given up hope when he saw lightning in the distance. Knowing that likely meant rain, he set off towards the storm, taking off his clothes, spreading them on the ground to catch the rain and sucking the water from his wet clothes.

For a further three weeks he struggled on until, on July 20, 1796: “I saw with infinite pleasure the great object of my mission – the long sought for majestic Niger, glittering to the morning sun, as broad as the Thames at Westminster.”

Park followed the river downstream for about 100 miles but as it was now the rainy season he soon decided that this course could be fatal as he had no idea where he might end up.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRetracing his steps, sometimes in company, sometimes alone, suffering from malaria and being reduced to begging for food in a country experiencing famine, he again resigned himself to death when he arrived on September 16 at the town of Kamalia.

Here he happened to meet Karfa Taura, a slave trader, who, for the promise of the value of a healthy adult slave, offered Mungo help and shelter and the promise of joining him with a slave convoy to the coast after the end of the rainy season.

On April 19, 1796, Park set off on the 500 mile trek to the Gambian coast.

Arriving there on June 20 he caught a ship bound for the West Indies from where he caught a ship back to Britain, arriving on December 22, 1796.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDuring his travels Park was able to experience first-hand the evils of the slave trade. While there is evidence to suggest he was opposed to it, he was never a vocal supporter of abolition.

The most likely reason for his silence? Influential members of The African Association were men whose wealth was based on slavery.

Park stayed in London where the publication of his account of his travels made him a celebrity.

Eventually, he returned to the Borders where he married Ailie Anderson and found work as a doctor in Peebles.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHowever, he was desperate to return to Africa and complete his exploration of the River Niger.

And in January 1805 Park left Britain for his second expedition.

Gone was any attempt at trying to be conciliatory. This time he was Captain Mungo Park at the head of a detachment of almost 40 heavily-armed soldiers.

The size and nature of the detachment drew suspicion and hostility from the native Africans and they received very little support.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe party set out in the rainy season and many of the troops died from fever. By the time they reached the Niger in August 1805 only 11 of the Europeans remained alive.

In October, with his party now reduced to just four soldiers and two Africans, they set off down the Niger in a roughly constructed boat hoping to reach the coast.

Park wrote what was to be his last letter to his wife just a month later.

It read: “We have already embarked all our things and shall sail the moment I have finished this letter ... You may be sure that I feel happy at turning my face towards home.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“We this morning have done with all intercourse with the natives; and the sails are now hoisting for our departure for the coast.”

The party travelled 1000 miles downriver but their “shoot first” policy meant they were met with hostility.

Eventually at Boussa, while being attacked, their boat was caught on rapids.

Attempting to escape, Park jumped into the river and drowned.

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.