Tweed fossils solve million-year mystery

The collection, including specimens discovered along the River Tweed, feature in a new exhibition at the National Museum of Scotland entitled Fossil Hunters: Unearthing the Mystery of Life on Land.

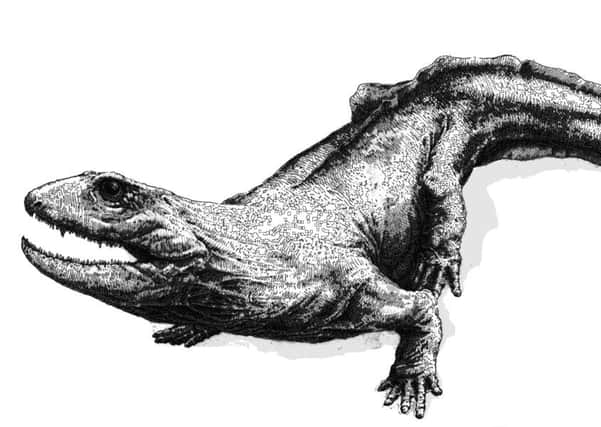

These groundbreaking finds from the Borders fill a major gap in our understanding of evolution. Until recently, there was very little fossil evidence of life on land during the early Carboniferous period, around 345-360 million years ago. This was a pivotal moment in evolution, when vertebrate life moved from the sea to the land, a momentous shift without which humans would not exist today.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis 15-million-year ellipsis is named ‘Romer’s Gap’ after the American palaeontologist Alfred Sherwood Romer, who identified it. Without evidence to the contrary, some palaeontologists concluded that low levels of oxygen during this period restricted evolution on land. However, these fossils confirm that a rich and diverse ecosystem of amphibians, plants, fish and invertebrates thrived during this period. Most importantly, they address one of palaeontology’s big unanswered questions, that of how vertebrate life crawled out of the water.

Visitors to the exhibition will have the opportunity to discover how amphibians took their first steps on to land and why this is such an important milestone in the evolutionary timeline. They will also be able to find out about the techniques used to unearth the fossils and what the extensive analysis of the finds tell us about life on land before the dinosaurs.

Nick Fraser, Keeper of Natural Sciences at National Museums Scotland said: “National Museums Scotland holds one of the finest collections of fossils of early, land-based life in the world. Solving the mystery of this evolutionary missing link is hugely exciting, and has allowed us to gain a rich understanding of a key period in the evolution of life on earth. This fascinating exhibition will explore in detail for the first time the full story of this remarkable discovery.”

Long before vertebrates evolved legs, there was already life on land. The earliest known terrestrial ecosystem in the world is preserved in a bed of sediment in Aberdeenshire called Rhynie Chert.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis 410-million-year-old rock contains plants, spiders and the oldest-known fossil insects.

However, there was no evidence of tetrapods (vertebrates with four limbs) on land. Fossil evidence pre-dating Romer’s Gap showed tetrapods living in the water 360 million years ago, but their limbs were not strong enough to support them on land. 15 million years later, ample evidence of tetrapod life on land can be found, by which point amphibians were well-adapted to walking. Palaeontologists could only speculate as to how and why the monumental step from water to land was taken.

The late Stan Wood, a self-taught field palaeontologist from Selkirk, was convinced that fossil evidence of tetrapod life during Romer’s Gap could be found in Scotland, and spent 20 years searching for it.

Finally, in 2011, he uncovered never-before-seen fossil evidence of early tetrapod life on land - fossil animal skeletons, along with millipedes, scorpions and plants- at the Whiteadder River, near Chirnside.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdStan, who also found fossils at Burnmouth and near Coldstream, said at the time: “There are a couple of hundred fossils in total from these sites and they give us an understanding into that part of the Earth’s history of which we knew next to nothing. The fossils found represent an entire community which is extremely important in understanding this period.”

These finds – some of which were displayed at the National Museum of Scotland in 2012 - were the catalyst for a major research project which set out to uncover further evidence of tetrapod life on land during the earliest Carboniferous period, and to analyse the findings. Fossil Hunters also presents subsequent fossil finds and detailed analysis alongside Stan Wood’s extraordinary discoveries.

Renowned BBC broadcaster Sir David Attenborough lauded the find, saying: “One is accustomed these days to hear of sensational new fossil finds being made in other parts of the world. But to learn of a site in this country which must surely be counted among the most extensively explored, in geological terms is wonderful and exciting.”

The research behind the exhibition is part of a major grant funded by the Natural Environment Research Council and the Heritage Lottery Fund, with research conducted by National Museums Scotland in partnership with the Universities of Cambridge, Southampton and Leicester as well as the British Geological Survey.